The Off-Center Seat: 55 Years of Myth Making

Facts.

In today’s post-truth, fact-challenged world, just what, in fact, is a fact?

Let’s consider this tweet by the makers of the 2021 series The Center Seat: 55 Years of Star Trek, which states:

Get all the facts behind the phenomenon with the new series, The Center Seat: 55 Years of Star Trek, OUT NOW on @history.

Now, note the subtitle of its companion book is The Center Seat - 55 Years of Trek: The Complete, Unauthorized Oral History of Star Trek.

Spot the difference?

The latter plainly advertises itself as an “oral history,” the series does not.

Oral history relies on interviews with people who have direct and personal experience/memories of an event.

With that in mind, let’s look specifically at The Center Seat episode one, “Lucy Loves Star Trek.” It offers a smattering of extremely brief oral history soundbites from a scant few veterans of the Star Trek production, a few snippets of archival clips, and (perhaps obviously) no one from Desilu.

But what results when the people with such personal experience are no longer with us? Can you have an oral history if they are not the primary subjects interviewed? Absent the people who’d “been there, done that,” the episode falls back on second-, third- or nth-hand accounts by people who weren’t there.

In the case of “Lucy Loves Star Trek” the bulk of those telling the story are, as the book’s description paints them, “Trek fandom’s top analysts.”

Oral history this is not.

So what do you call that?

That’s oral tradition.

Yes, there’s a difference.

Oral tradition passes collective memory from people who do not have direct experience of an event, generation to generation, putting such memories on the path to becoming myth and legend.

And this is just what “Trek fandom’s top analysts” give us in spades. Despite their heartfelt love of the material, most are largely repeating things they’ve read and heard, occasionally misremembering, frequently embellishing, and sometimes outright misrepresenting events…events for which there are, in many cases, documented sources. Many have no access to those documents or—in a few instances—had access, but either did not review their notes or even their own works before sitting for an interview.

To further complicate matters, those interviewed aren’t really permitted to speak for themselves, their every comment framed and shaped by scripted narration, cutesy episode clips, and rapid-fire editing, which reduces every contribution to a soundbite.

Finally, as enthusiasts, some are necessarily invested in and married to the mythology that’s grown up around Star Trek; a mythology some have made a business via books, podcasts, and fan magazines. The result: as Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell said in 2016, “The stories get better the more I tell them.”

Can we reasonably expect the end result to resemble “fact”?

In a word: no.

With that caveat, let’s take a hard look at The Center Seat‘s debut segment, “Lucy Loves Star Trek,” and see how close its oral tradition conforms to historical documents, first-person accounts, and contemporaneous media coverage.

Format

We’ll present quotes from the show in the following format:

All program quotes will appear in shaded boxes of this color.

Quotes by the narrator will be presented without quotation marks.

“Quotes by on-screen interview subjects and archival clips will be presented inside quotation marks.”

For brevity and clarity we will largely be picking out key statements whilst omitting the cutesy episode sound bites, etc.

We’re also not going to I.D. the speakers in most instances because the program is terribly edited and we suspect some of the mistakes are soundbites used in the incorrect context, and it’s unfair to pillory the speakers for the mistakes of the filmmakers.

So without further ado, let’s rip through the upholstery of The Center Seat episode 1.

President Lucille Ball & Executive Vice President in Charge of Production, Oscar Katz at the August 18, 1964 Desilu Board Meeting, while Star Trek’s first pilot was being developed. (Los Angeles Times Photographs Collection, UCLA)

DesiLucy

“I Love Lucy became number one six months after it debuted in 1951.”

“And it was huge. It was like 67 million people were watching this. You know, at the time, not everyone owned a television set. Many people were watching in appliance stores.”

Ratings are…tricky.

While it appears to be true that I Love Lucy reached #1 in its first season[1] the “67 million” number is an error. Lucy achieved a 67.3 Nielsen rating during its second (1952–53) season[2] for the episode “Lucy Goes to the Hospital.” That was not the show’s average audience size.

A Nielsen rating does not indicate the number of viewers. Rather, it is the percentage of total TV sets (on or off) tuned to a given program. The number of total people watching that peak performance—not its season average— was closer to 44 million, ~50% fewer people than stated.

As to people watching in appliance stores, such things were not being tracked. This is only really happening in our modern age.[3][4]

“No one thought of reruns. There was no such thing. Something aired and then it was disposable, you never saw it again.”

In actual fact , reruns predate I Love Lucy. Reruns were an established practice in radio and TV well before I Love Lucy. The term is used in the trades at least as far back as 1949.[5] Lucy was a notable success in reruns, but it didn’t originate the practice.

"CBS doesn’t want to stop airing it during the summer. They say, ‘Can we have those reruns back?’ [...] And they had to pay Desi Arnaz a million dollars to get the rerun rights back for that summer.”

CBS didn’t rebroadcast any episodes of I Love Lucy the summer after its inaugural season (1951-52). For 14 weeks it was replaced by My Little Margie.[6] We’ll address the “million dollars” in a moment…

And with that cool million, Desi and Lucy…

“She used that money to buy RKO.”

CBS actually paid Desilu a cooler 4.3 million…and that didn’t happen after the first season in 1952. The deal was completed in 1956, and the final sale price for RKO was $6,150,000.[7]

“She said, ‘Bring me a show that can rerun as long as I Love Lucy.’”

Throughout the program the talking heads put words in people’s mouths. Lucy might have effectively said this, or her choices implied it, but is it a quote? Is it documented? No. Too often its interview subjects are imagining what people like Lucy were thinking or saying. Statements like this are of the “she’s like, 'bring me a show’” variety, and not in any way historical.

Keep that in mind going forward.

Enter the Bird

The program moves from Lucy and Desilu to the Great Bird of the Galaxy himself, Gene Roddenberry.

“He [Roddenberry] was on a Pan Am jetliner that crashed in the middle east.”

Jetliners weren’t in service at that time. Roddenberry was dead-heading aboard a Lockheed L-049 Constellation "Connie" propellor-driven “airliner”, not a “jetliner”. Pan Am wouldn’t commence commercial jet service until 11 years after the crash.[8] This is a small point but demonstrates of how details drift when repeated off the cuff.

“Gene Roddenberry, this budding writer/producer, wrote a script for Have Gun—Will Travel. [...] He wrote a ton of scripts.”

Roddenberry didn’t write just a script for Have Gun—Will Travel, he wrote 24 episodes of it and even won a Writers Guild Award for one (“Helen of Abajinan,” first aired December 28, 1957).

He did indeed “write a ton of scripts,” but a notable one early in his career is omitted: his first science fiction piece, The Secret Defence of 117 (aka The Secret Weapon of 117), starred Ricardo Montalban and aired in 1956.[9] (We’ll be reviewing that script soon.)

Roddenberry’s first sci-fi program, and (apparently) first professional notice, gets zip mention in The Center Seat.

“And [Roddenberry] does land his own show called The Lieutenant. It’s about a Marine Corps officer who’s a lawyer.”

The titular character of The Lieutenant—William Tiberius Rice (Gary Lockwood)—was not a lawyer, though the show contrived to have him act as one in the episode “Fall from a White Horse,” much as Riker and Picard were in Star Trek: The Next Generation’s “The Measure of a Man”.

“Gene Roddenberry, he wants to do hard-hitting adult themes. One of his episodes is about racism. [...] It brings him head-to-head in battle with the network, with the studio.”

This hard hitting episode was ahead of its time. NBC wouldn’t give it the time of day, or even a time of day in its schedule.

“It winds up not even being shown.”

The episode in question, “To Set It Right,” was controversial with the Marine Corps, which pulled its official seal off the episode.[10] But our searches of the trades and newspapers indicate it was aired…and even rerun. Heck, Roddenberry himself said it aired![11]

The supposedly unaired episode of The Lieutenant…which Roddenberry himself said did air. Note also, The Defenders episode concerning drug dealers.

Let’s briefly talk about how progressive or regressive American TV could be at the point The Lieutenant aired. The 1968 book The Making of Star Trek has this to say about the climate in the mid-60s:

For some reason television seems to run in cycles. At that time, programming was nearing the end of the "true-to-life Defenders" type of cycles. All trends indicated a cycle back to action-adventure. This cycle later spawned such shows as "I Spy" and "The Man From U.N.C.L.E." When Gene suggested he'd been playing with a science-fiction adventure script idea, MGM expressed a willingness to look at it.[12]

And this is a fair assessment. The Lieutenant was made—and Star Trek conceived—during the tail end of an era of hard-hitting “true-to-life Defenders” shows like East Side/West Side, Slattery’s People, and the Emmy juggernaut, The Defenders on CBS. The latter earned 22 Emmy nominations and won 14. It was a top 20 show[13] that tackled controversial subjects like the death penalty, police vigilantism, and even teen pregnancy and abortion as far back as the 1961-62 TV season.

This is not to say just any program could address controversial topics, but such shows were not entirely absent in the era of The Lieutenant.

Trek enthusiasts will constantly beat this drum, but the fact is that neither Roddenberry’s The Lieutenant nor Star Trek were pioneering such content.

Trekking to Desilu

"1965, he finally puts the ideas to paper. He’s going around to the networks."

Which didn’t take long, actually, because—

"In the early sixties, there were only three networks.“

And they all passed.

“He [Roddenberry] gets turned down everywhere.”

1964, not 1965. The first pilot was filmed at the end of 1964.

Fans, and programs like The Center Seat, routinely conflate studios with networks. Gene had to sell a studio on the idea, and only with a studio’s backing could it be pitched to a network.

And as to studios, how many were approached is unclear. It’s been written that both Warner Bros. and Columbia (Screen Gems) rejected Star Trek, but we’re unaware of any documentary evidence to support this.[14]

However, on April 24th, Gene registered the series prospectus at the Writers' Guild of America, West, Inc. to protect the concept of Star Trek from theft,[15] and just six working days later, on May 4th, Roddenberry was meeting with (Executive Vice President in Charge of Production) Katz and Solow at Desilu, Katz having previously seen the pitch. Unless Roddenberry was shopping Trek around unregistered, which seems unlikely, that’s not a lot of time to pitch to other studios…although he could have been investigating other avenues even while negotiating with Desilu.

However, David Alexander's authorized bio of Roddenberry indicates that after MGM expressed no interest, Roddenberry went to Desilu studios next. This is supported by what Roddenberry wrote to Alan Courtney (an MGM executive):

During the same time, although I have been gratified at the interest you have shown in my science fiction series presentation, Star Trek, and have received similar comments from others at MGM who have read it, my agency Ashley-Steiner has received no indication of MGM interest. In the meantime, interest has developed elsewhere and Ashley-Steiner, as they properly should do in such a case, has begun discussions there.I thought it only proper to let you know that these discussions are moving so rapidly that I may very quickly have to give an answer to some firm offer.[16]

Further, his agent’s agency had a deal with Desilu, so where would he have most likely have been sent next?

As to networks, the documentary evidence makes it clear the only networks ever pitched to were CBS, which declined, and NBC, which bought it. ABC was never approached.[17][18]

What these commentators in the program are doing is, frankly, pandering. They’re selling the legend of Star Trek as this ugly duckling that mere mundanes couldn’t see was destined to be a beautiful swan.

Perhaps the first mention in the trades of what we know became Star Trek, first pitched at MGM.

“They [NBC] wanted to do business with Lucille Ball, because Lucille Ball was CBS’ golden girl.“

NBC’s reported desire to work with Lucille Ball on Star Trek appears to have been popularized by former Desilu executive Herb Solow, who wrote in Inside Star Trek that:

NBC wanted to have a Desilu show on their network. They had never had a series from this studio. As a matter of fact, they had never even had a development deal with Desilu.[19]

Solow’s claims about NBC having no relationship with Desilu is, strictly speaking, not true. Previous to Star Trek, Desilu had sold the game show You Don’t Say! to NBC, where it aired on the network’s daytime schedule from 1963 until 1969. NBC had also bought eight new episodes of Kraft Mystery Theatre from Desilu when it aired it as a summer replacement series in 1962.

NBC was absolutely interested in poaching top talent from CBS. The network did just that with Alfred Hitchcock, Danny Thomas, and Jack Benny, who all left CBS for more lucrative deals at NBC beginning with the 1964-65 season.[20] For a few weeks in early 1964, Lucy indicated in the press that “she will no longer submit to the rigors of a weekly television series, preferring to devote her time to production at Desilu studios”—in effect, putting CBS’ top-rated The Lucy Show on the potential chopping block.[21] However, by early March of 1964, Ball had reversed course, signing a new three-year contract with CBS to continue The Lucy Show. By the time Star Trek was being pitched to Desilu, any chance NBC had at CBS’ golden girl had been dashed.

So, given this, why would NBC want a Desilu show on their network given:

a) Lucy would not come with it, and…

b) At that time Desilu was not perceived as a “player” in original program development

Scrutiny, friends. Scrutiny is important when considering claims of this nature.

“This frumpy guy, very soft spoken, very mild-mannered, came in with this single piece of paper and his memo about what Star Trek is.”

We suspect this is a “telephoned” version of what Herb Solow wrote of his first meeting with Roddenberry:

He smiled boyishly and mumbled, Hi, I’m ... ahh ... Gene Roddenberry. Ahh ... Alden sent me.” He handed me a piece of paper wrinkled in the corner by his nervous fingers. “This is a series idea I have. It’s ... ahh ... like Wagon Train to the ... ahh ... stars. It’s called ... ahh ... Star Trek.”[22]

But Solow’s account is dubious. A detailed letter from Roddenberry to his agent Alden Schwimmer the day of the meeting (and, according to the trades, Solow’s first day on the job) makes plain Schwimmer was in attendance, as was Oscar Katz.[23] Further, the Star Trek pitch was already pages long before Roddenberry left MGM.[24] So what was this one page? A summary?

In any case, this is oral history cum oral tradition cum (likely) faulty memory.

“A Wagon Train to the stars.”

“Wagon Train being a very popular Western anthology series.”

“Headed to the frontier, running into different obstacles.”

As it had continuing leads, but the setting and the guests were completely different each week, Wagon Train was no more a full blown “anthology” than Star Trek. Both shows were—like the series Route 66—a hybrid between episodic television drama and anthology.

One key thing everyone misses about Wagon Train as Roddenberry’s go-to was not its format per se or that it was a western, but that it was known as a prestige drama with a cast of regular characters who would meet and interact with members of the wagon train, often played by big name guest stars.

Wagon Train could be shorthand for “quality TV”.

Lucy liked what she heard, and Desilu decided to board this wagon train.

”So that put Desilu back in business as far as owning properties.”

“This wasn’t just for Gene Roddenberry, this [Star Trek] was something that could be the salvation of Desilu.”

This makes it sound like Desilu was putting all its eggs in Star Trek’s basket. While Trek was one of the—if not the—first pilots Desilu started developing under new Executive V.P. Oscar Katz, it was not the only one in the works. In fact, barely four weeks after Roddenberry and Schwimmer met with Oscar Katz and Herb Solow, Desilu was crowing him as one of three producers or producing partners signed to the studio.[25] And by August, Desilu had five pilots in development: three for NBC and one each for CBS and ABC. (The cave set for one sitcom, The Good Old Days, was suggested for possible use in Trek’s first pilot as the Orion corridors.) Ultimately, none of them got series orders, but Star Trek got a second chance.

“Lucy had a development fund. She gave them money from the development fund to develop Star Trek.”

With Lucille’s own money, Gene began scripting his Wagon Train to the stars, starting with his lead character.

Bzzzt. Wrong.

Firstly, NBC put up story money for Star Trek, so they were funding part of the pilot script development.

Secondly, this myth about the development fund being used for Star Trek seems to have originated with Joel Engel’s unauthorized biography of Roddenberry,[26] and reinforced two years later by Herb Solow, who wrote:

CBS countered [...] establishing a major development fund for the studio’s use, and Lucy began to develop new series [...] CBS represented our best shot, because of Lucy and, more significantly, because it was their development money we were playing with.[27]

But Solow appears to be wrong about this fund financing Trek.

Yes, the fund was paid for by CBS, but an internal document comparing costs of Desilu’s shows after the Paramount merger makes it clear that while this CBS-paid fund was used to largely finance the Mission: Impossible and Mannix pilots for CBS, it was not used for Star Trek.[28]

Mickey Rudin told Daily Variety on August 17, 1966 about terms with CBS established for I Love Lucy’s fifth season:

He said that terms for the program’s fifth season gives Desilu a $600,000 war chest to be used exclusively for new program development, indicating this kind of network aid is not available to major or independent vidfilm production companies. Similar deals must be forthcoming from NBC and ABC, he said, before Desilu would undertake new projects for them. Rudin also said that a special option clause guaranteed Desilu at least $6,600,000 additional income on reruns of “Lucy.”[29]

Days later Broadcasting magazine reported on the previous week’s Desilu shareholder meeting:

Stockholders also were told that Mission: Impossible and Star Trek, the two shows Desilu sold to CBS -TV and NBC - TV, respectively, for the 1966 -67 season did not come out of the CBS pilot fund but at least two and maybe three pilots for the 1967 -68 season will be financed by the $600,000 that has been set aside.[29a]

These accounts differ on Mission, but both agree that the fund was not used for Trek.

This further suggests that the development fund was for CBS projects—not for pilots for NBC or ABC.

"NBC was saying, 'You’ve got to find a way to make Americans feel comfortable in space. Well, let’s build something around them that all America is familiar with.'"

Remember what we said about putting words in people’s mouths?

This is a prime example. This did not come down from on high. The document trail makes clear Gene walked into Desilu with this already planned. It’s all in the pitch he wrote at MGM. Herb Solow gives Gene complete credit for originating this concept, long before any network was pitched. Per Solow:

And he'd solved one of the problems of audience familiarity by using contemporary navy terms, ranks, names, and jargon. It was captain and yeoman and medical officer; it was 'starboard' and 'port,' and it was the U.S.S. Yorktown (later changed to the Enterprise), rather than 'Rocket Ship X-9.'"[30]

“He [Roddenberry] had his wish list of who he wanted to play the Captain of the Enterprise. And right at the top of that list is William Shatner."

We know of no reputable source that would support this claim.

Even if true, Shatner was signed to the series For the People in September 1964, and Star Trek’s pilot casting ramped up in October, so it makes sense that Shatner isn't listed on most of those docs.

A mid-season replacement, premiering January 1965, For the People was short-lived at 13 episodes, freeing Shatner to accept the role of Captain Kirk when Star Trek’s second pilot filmed in July.

Shatner’s name does appear right near the bottom of a single undated first pilot casting memo in the Roddenberry papers at UCLA. We suspect that one might’ve been an early “wish list”.[31]

Even Shatner’s own memoir does not portray him as the producer’s first choice, claiming that Roddenberry offered the first pilot to Lloyd Bridges before Jeffrey Hunter, and the second pilot to Jack Lord before Shatner finally got the part.[32]

Nimoy had just finished perfecting his contemplative demeanor on The Lieutenant.

While this narration is a bit tongue-in-cheek, and the clip shown has Nimoy silently contemplating, his character in The Lieutenant (episode “In the Highest Tradition”[33]) is a gregarious Hollywood producer. Decidedly not contemplative and utterly unlike Spock.

See for yourself…

“The [first] pilot had cost, I think almost $600,000, which would be like $6 million today. And NBC only put up half the money, Desilu put up the other half.”

A 1968 cost-revenue analysis puts the 1st pilot total cost at $615,751, of which NBC put up exactly $185,000.[34] Thus, the finished pilot cost $430,751 over NBC’s contribution, but that was Desilu’s decision.[35] (The total is actually fairly close to what Lost In Space’s pilot—shot the same month as Trek’s—apparently cost.)

“Lucy reached into her pocket to refinance the pilot, do a new one.”

First of all, “refinance the pilot” makes no sense, Desilu agreed to co-finance the second pilot NBC had ordered, not “refinance” one.

Second, we love Lucy, but these kinds of statements about “her pocket” and “her money” somewhat misrepresents how businesses work. Desilu was a corporation with stockholders in which Ball held the majority stake. She got dividends, but the company’s money was only “hers” in a figurative sense. This is an important distinction.

According Desilu’s Bernie Weitzman, re the CBS developmnt fund:

“She could either put half of it in her pocket and do nothing, or spend the whole fund doing programs for Desilu, with CBS having first crack at them. We had $600,000 spelled out.” [35a]

Good businesswoman that she was, Lucy chose to put the studio first, so even in that case the money never went to into “her pocket.”

For more on Lucy and Desilu see our 2020 piece Lucy Loves Star Trek?

Meanwhile, Gene suddenly found himself in need of a doctor, because John Hoyt had gone off to do movies [...] Opening the door for Gene’s first choice, DeForest Kelley, who finally landed the role of Bones by giving the execs a look beneath his hat.”

According to Herb Solow, after the first pilot NBC wanted to wipe the slate clean with the cast, and was only willing to keep Hunter and Nimoy, so Hoyt (Doc Boyce) was airlocked along with everyone else, not merely because he had movies to do.[36]

As to Kelley, the program is discussing the second pilot here, not the series, and DeForest Kelley wasn’t the doctor in the second pilot, Paul Fix was (as Doc Piper).

Kelley was cast in Roddenberry’s Police Story pilot, which shot immediately after Trek’s second pilot. See our article “The POLICE STORY Story (link)” for more on that show.

This is one of several cases where the episode confuses the order of things. The Department of Temporal Investigations should be notified forthwith…

Furthermore, Kelley was not an unfamiliar face at NBC outside westerns. He’d previously appeared in two unsold Roddenberry pilots for the network: as the lead—a lawyer—in 333 Montgomery (1960)[37] and as a police lab chief in Police Story (filmed 1965, aired 1967)[38]. It was the latter which likely cinched him the role.

“Jeff Hunter was offered a movie.”

Unsubtantiated.

The Making of Star Trek claims Hunter “was making a motion picture and was unavailable”[39] for the second pilot—but there’s zero evidence to support this. Oscar Katz tells a different story (see Oscar, Where Are You? Part I). It’s possible Hunter didn’t want to be tied down to a weekly series again, after having been the star of Temple Houston. We’ll have more to say about this in a future piece.

Startup SNAFUs

The [second] pilot cost a whopping $450,000. NBC thought the budget should be more in the orbit of $185,000. [...] And even at that price, the network wouldn’t be footing the entire bill.

“It’s deficit financing. The networks do not pony up all the costs of a show.”

More confusing presentation, again conflating the network (NBC) with the studio (Desilu), this time over the total pricetag of the pilot. What they appear to be inarticulately relating is that the cost of the second pilot wasn’t what anyone thought the episodes should cost. This is a big “well duh.” Due to start-up costs, pilots are almost always more expensive than regular production episodes.

July 19, 1965. Oscar Katz and Herb Solow kid Roddenberry about the production of Star Trek’s (ultimately successful) 2nd pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

Anyway, to clear up this confusing mess, for the second pilot NBC actually increased their investment by 13% and ponied up $209,000.[40] The $185,000 figure is roughly what Desilu itself budgeted as the average cost per-episode when the budget was cut at the end of the 1st season (when it was dropped by ~$7,000 per segment).

NBC would only back Star Trek to the tune of $100,000 per episode.

"So Desilu is going in the hole $85,000 with every episode they’re making.”

Liar liar pants on fire.

NBC never paid a licensing fee of less than $140,000, 40% more than claimed, and that fee went up every year.

In the first season, when you add in foreign sales and the license fee for on-network reruns—and subtract Ashley Famous’ 5% commission, foreign distribution costs, and network repeat costs—against an average episode budget of (initially) $192,373 (that was lowered to $185,349 near the end of the season), the studio was actually deficit financing something closer to $26,308 per episode (dropping to $19,284 when the budget was cut).

That’s still a lot of money but more than three times lower than the figure claimed.

In fact, by the end of Star Trek’s run NBC was paying $160,812 out of the average episode budget (slashed by Paramount) of $178,362, which meant NBC was paying 90% of the average 3rd season budget, leaving the studio (now Paramount) only deficit financing $17,550 per segment. When we factor in all the other fees and revenues, during the third year, it appears the studio was bringing in more net revenue per episode ($185,004) than the average official budget per episode.[40]

Yes, we’ve looked at the actual paperwork. You’re welcome.

“She [Lucy] said, ‘Let’s go ahead and produce the whole thing.’ She’s like, ‘I’m putting the fate of the studio in your hands, guys.’”

Again, this oral tradition is making up words to put in the mouths of these figures. There’s no record of what Lucy might have said. And word choice carries weight. Of those words, “fate” is a loaded one; ”future” might be more accurate.

See our piece Oscar Where Are You? Part I for an actual oral history on the state of Desilu in 1964.

With all that pressure, Gene decided to recruit a Gene 2.0. Coincidentally, also called Gene.

“He was really in charge of the writing room. And he was very interested in making sure that the characters were the most important and central thing.”

Intentionally or not, The Center Seat’s narrative implies that Roddenberry hired Gene L. Coon as soon as Desilu committed to making Star Trek as a weekly series. But this ignores and erases the contribution of John D.F. Black, who worked on the series (credited as associate producer, Black’s main responsibilities were handling rewrites, reading unsolicited material, and otherwise dealing with freelance writers) from April 12 through August 14 of 1966. It was Black’s departure that left the vacancy that Coon filled (Coon’s start date was August 15, 1966).

And there was no “writers room” on Star Trek. Dramas were typically not room-written in that period, as is commonplace today. The only writers on staff were the producers, maybe an associate producer, and the script consultant/story editor, who wrote and did rewrites, but the majority of episodes were assigned to freelancers. This is borne out by the wealth of story memos generated in the 1st and 2nd seasons.

“The very first episode, 'The Man Trap,' 47% of the TV’s in America were tuned in.”

Not accurate. We went into this years ago in the article The Truth About Star Trek and the Ratings, but we’ll sum up here.

For its first 15 minutes only, “The Man Trap” received a 46.7 share, but by its last 15 minutes, the show had shed nearly 10% of its audience, receiving a 39.8 share.

The show’s actual Nielsen rating started at a 25.2 and finished at a 23.0. Which means that, at its height, 25.2% of television households (sets on or off) were tuned in to Star Trek.

Also, Trek’s premiere was against extremely weak competition, mostly reruns and a single new program that was “one of television’s most famous flops” (link), broadcasting only four episodes before being yanked. By its fifth episode Trek had dropped to 51st position in the ratings, and hovered in that area throughout the remainder of the season, finishing the year at #52.

Tall Tales of the City

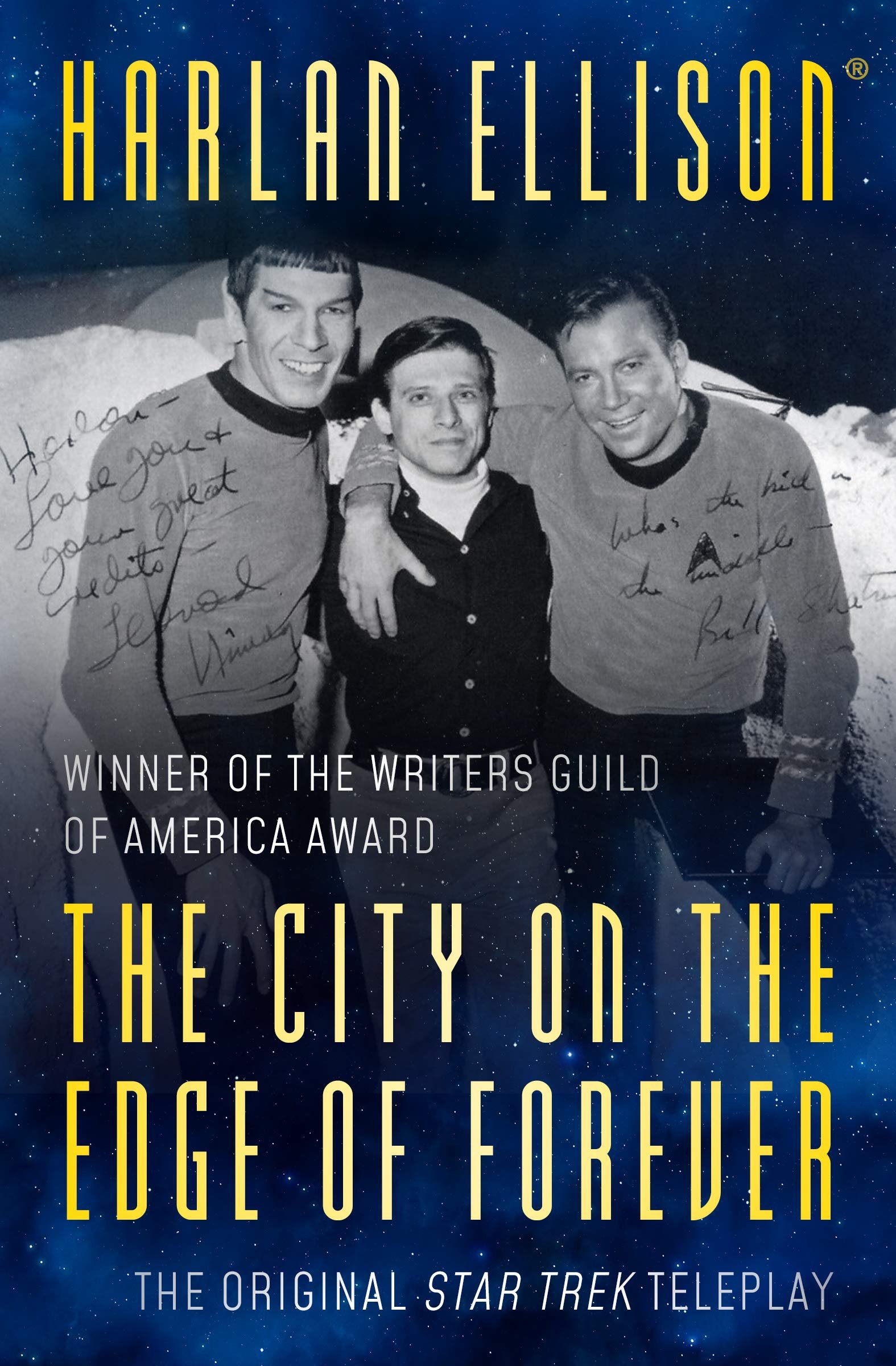

As shown in this photo, Ellison (presumably) snuck out of Justman’s office to visit the set of “Mudd’s Women” which filmed Jun 2–13, 1966, two months before Gene Coon joined the staff.

The entire section of the program regarding “The City On the Edge of Forever” is out of order and confusing. So allow us to clear up the sequence of events.

Ellison received the assignment to write his episode very early, but was slow in delivering, so Bob Justman encouraged him to write it on the Desilu lot, eventually in his own office. Ellison did, delivering the first draft teleplay in June, then, after a protracted delay, submitted a “final draft” in August. There’s a lot more to it, but we have a whole piece planned on the episode’s genesis.

For now, let’s address some of the things The Center Seat gets wrong about this famous Trek segment.

“So Gene Coon made a bold, executive decision.” “[…]Coon locked him [Ellison] in a room.”

By most accounts, including Bob Justman’s,[41] it was Justman who did this. Coon wasn’t even on staff until August 15, 1966—two months after Ellison had turned in his first draft teleplay, and around the time he delivered his “final draft”.

“When she’s [Fontana] working on Star Trek, she’s actually the youngest story editor in the history of television.”

Fontana's screen credit wasn't "story editor" it was "script consultant." Which makes it even harder to verify this assertion.

Fontana herself wrote, “At twenty-seven, I was the youngest story editor in town and one of the few female writers on a series staff.”[42] Note she doesn’t claim to have been the youngest to have held such a position up to that time. It’s certainly possible Fontana was the youngest script consultant in town when she assumed the position on December 19, 1966. However, television was not new in 1966, so it is hard for us to say with certainty that no one her age or younger had ever held such a position since the dawn of television. We do know that Paul Playdon, named script consultant on Mission: Impossible on September 5, 1968, was only twenty-five when he landed the same job. Relatively few women were indeed working screenwriters in that era. Still, there were exceptions: notably Nina Laemmle was credited as a story editor as early as March 1958 on the series Richard Diamond, Private Detective, though she was almost 50 at the time.

Dorothy Fontana c. 1967.

“Dorothy Fontana came up with the part about McCoy accidentally injects himself. Goes strange.”

A longstanding myth but this bit of business appears to have been invented by Fontana’s predecessor, Steve Carabatsos, whose autumn ‘66 rewrite of “City” had McCoy accidentally shooting himself up with “Milekrin Adrenaline”. Fontana changed the name, but unless she suggested the idea to Carabatsos, she didn’t invent it. Sorry, Dorothy.

Before Fontana made it “Cordrazine”, Carabatsos invented “Milekrin Adrenaline.” Either way, an O.D. on the stuff is a bad time trip.

But Harlan Ellison’s “The City on the Edge of Forever” would come with a hell of a price tag, putting the whole series on the edge of forever.

”It was the most expensive episode of Star Trek, ever.”

While “City” was inarguably the single most expensive regular production episode of the series, going 28% over the average original first season budget (which was revised downward the day after lensing began on the episode[43]), it was not unique in being expensive.

Other budget-buster first season episodes included “Balance of Terror” and “The Galileo Seven,” over by 23% and 21% respectively.

“His [Ellison’s] script would have cost as much as a major motion picture.”

Hyperbole. We’ve read most of Ellison’s drafts (one is partial), and they’re not vastly larger in scope than the finished episode. Many scripts first came in too expensive and were cut back. Ellison himself cut several elements in the course of his rewrites.

As to “a major motion picture,” for perspective, 1956’s Forbidden Planet, an “A-picture”—adjusted for inflation—cost ~$2.34 million in 1966 dollars; 9.5x “City”’s final cost. The contemporary 1966 Batman movie had a budget of $1,377,800, and it was not a “major” motion picture. Even had Ellison’s version been twice the final episode price (it wouldn’t have been), it would have cost about what the 2nd pilot did; a third as expensive as Batman.

Ergo, to say Ellison’s script “would have cost as much as a “major motion picture” is an exaggeration bordering on an outright lie.

Seasonal Slipups

And that meant, season two of Star Trek really needed to turn those thrusters on. [...] Luckily, it was not only in color, but in a prime slot.

“NBC had promised Gene the 8:00 o’clock time slot on Monday and then they gave it to Laugh-In. [...] Because Laugh-In had gotten such strong ratings they didn’t want to lose the time slot.”

And so a comedy sketch show sent Star Trek to a distant galaxy.

“Ten o’clock on Friday nights.”

Of course Star Trek was in color. NBC’s entire primetime lineup was all-color by fall of 1966.[44] So what’s the point of mentioning that?

As to the rest…

Wrong wrong WRONG.

The program again completely botches the timeline.

Star Trek had been moved to Friday at 8:30 p.m. for its second season (1967-68). Laugh-In wasn’t a series then; its pilot was aired as a special on Sept. 9, 1967, and the series was ordered as a mid-season pickup, airing its first regular episode on Monday, Jan. 22, 1968, midway through Trek’s second season.

For its 2nd season Star Trek was moved to Fridays, but it would not land at 10 p.m. until its 3rd. Note that Laugh-In is not on the schedule at this point.

The reality is that the Laugh-In scheduling conflict was in Trek’s third season. There are contemporary reports that NBC did indicate they planned to move Trek to an earlier slot, including Mondays at 8 p.m. and then 7:30 p.m., but in the end kept the show on Friday and bumped it to the 10 p.m. time slot. (We dug into the reasons for this for our piece “The Flying Fickle Finger of Fate” here (link).)

(Interestingly, Laugh-In replaced one-time hit The Man From U.N.C.L.E., which had plunged from the top 20 to the mid-60s, finally demolished by the second half hour of Gunsmoke and Lucille Ball’s own The Lucy Show on CBS—and, to a lesser extent, the last half hour of Cowboy in Africa and the Rat Patrol on ABC. Ironically had Trek gotten U.N.C.L.E.’s slot, it would have been competing against Lucy herself![45])

In its 2nd season premier for the 1968–69 season, Laugh-In had some fun with its competition. The Lucy Show had ended, and Here’s Lucy was set to premier the following week opposite Laugh-In’s second half hour. Lucy’s new series landed at #9 for the season. Laugh-In hit #1.

But the way The Center Seat is edited, even if the interviewees telling the story got it right, the way the comments are cut up it sounds as if NBC moved it to the so-called “Friday night death slot” in its 2nd season, which is off by a year.

A. Year.

“Ten o’clock on Friday nights.”

”That was a bad time slot for Star Trek.”

“Gene knew nobody stays home and watches television on Friday night, that’s movie night, that’s date night.”

Or so says 50+ years of Trek mythology, and yet in its 1965–66 season The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was rated #13 overall with an average 24.0 rating in that very 10–11 p.m. “death slot” on Friday nights…on NBC. No one ever discusses that. Why? Perhaps because asking such questions would be an inconvenient truth to the oral tradition that’s been handed down as gospel for 50+ years.

Jack Davis’ spread for NBCs 1965–66 season pegs The Man From U.N.C.L.E. firmly in the so-called “Friday Night Death Slot” where it flourished with a 24.0 rating and ranked #13 for the season.[46][47]

“The network wanted a young character to appeal to the younger audience.”

“Thanks to a classic Roddenberry twist.”

“Let’s make him a Russian [...] And this was huge...for 1967.”

Was it “the network”? Or was it Roddenberry cashing in on “Monkeemania”?

to: Joe D'Agosta date: September 22, 1966from: Gene Roddenberry subject: NEEDED CREW TYPEKeeping our teen-age audience in mind, also keeping aware of current trends, let's watch for a young, irreverent, English-accent Beatle type to try on the show, possibly with an eye to him reoccurring. Like the smallish fellow* who looks to be a hit on "The Monkees." Personally I find this type spirited and refreshing, and I think our episodes could use that kind of lift. Let's discuss.Gene Roddenberry[48]

* Davy Jones

Further, the book Inside Star Trek also suggests the idea came from Roddenberry, adding…

Roddenberry intended to go where only one other TV show had gone before. Like The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Star Trek would have a Russian as one of the good guys.[49]

NBC or not, it wasn’t “huge” since, as above, it had been done…and on NBC. The Man from U.N.C.L.E.—which bowed in 1964—featured secret agent Illya Kuryakin (David McCallum), who was the show’s breakout character (effectively their Spock), promoted to co-lead, and became a teen heartthrob. Kuryakin was always referred to as Russian (though the character was said to have spent part of his childhood in the Ukraine).

No one ever seems to consider if this character’s appeal influenced the decision to create Chekov.

The Man From U.N.C.L.E.’s “Russian” co-lead was already an established teen heartthrob before the November 19, 1965 date of this cartoon by Bob Keane (best known for Family Circus).[50]

This is a fine example of how easy it is to get TV history wrong by narrowly focusing only on the subject itself and missing the broader cultural milieu and media landscape it existed in, both of which inform the story.

Fan Service & Fan Fictions

With Star Trek seemingly on life support, thousands of fans picketed NBC demanding they not pull the plug.

“We got a million letters.”

There’s so much mythology around the various letter writing campaigns that it’s tough to sort out.

The first, during the first season, was spearheaded by Harlan Ellison and “The Committee” of SFWA (Science Fiction Writers of America) members (Poul Anderson, Isaac Asimov, Robert Bloch, Lester del Rey, Philip José Farmer, Frank Herbert, Richard Matheson, Theodore Sturgeon, and A.E. van Vogt). It capitalized on the SFWA mailing list to try to generate response. And in its aftermath, at least one fan was already speculating that it must have generated “close to a million” letters, a figure repeated in the 1975 book Star Trek Lives!

The second was the now-legendary ”Save Star Trek” campaign, which kicked off in Dec. 1967, initially by Bjo and John Trimble.

Oh, and there are newspaper items from early 1969 about some fans trying again.

The “million letters” claim is widely repeated but unsubstantiated…for any campaign. As above, the number gets mentioned for the first campaign, but where it appears most often is in news items published at the top of 1968, in response to the aforementioned “Save Star Trek” campaign.

Inside Star Trek pegs Trek’s total mail count to NBC for Jan-Feb 1968 at 12,000 pieces.[51] A March 17, 1968 news item pegs the number at 114,667.[52] Newsweek magazine reported 16,000 letters as of late January, 1968, including one petition which supposedly bore 1,764 signatures.[53] Various other news items give wildly divergent numbers.

It turns out that NBC did comment on the mail volume following the “Save Star Trek” campaign. The office of V.P. Mort Werner—the man reportedly responsible for giving Trek its second pilot shot—wrote to TV Guide magazine, saying:

[…]more than 100,000 viewers—one of the largest totals in our history—wrote or wired their support for Star Trek.[53a]

Note this letter didn’t specify individual letters or wires (presumably telegrams), so some of these signatures may have been from petitions. He also doesn’t indicate if this was the total received by NBC itself, or if that figure includes letters and wires reported by network affiliates. But in whatever case, that’s about as an official acknowledgment of the campaign as we’ve ever seen, even if the figure is 10x lower than the “million” claim.

NBC’s Mort Werner addresses the letters

Supporting Werner, in August of the same year, Roddenberry is quoted as saying:

The network got over 100,000 pieces of mail, over 1 million signatures—and many signatures NBC could not disregard.[54]

Note he mentions “signatures,” which also suggests petitions.

So it’s possible and perhaps even likely that people have conflated signatures with letters, leading to the unsupported “million” letters.

(For the record, a million letters at average weight would come in at 12.4 tons, or 11.25 metric tons.)

We’ll get into the campaigns themselves at a later date.

Now, on to those protests…

There are no records of “thousands of fans” picketing NBC. The Cal Tech protest reportedly numbered 200–300.[55]

Regarding “thousands of fans” picketing NBC, this number seems to be exaggerated. The Los Angeles Times reported that “nearly 300” fans joined the protest at NBC Burbank in January of 1968.[56]

Roddenberry repeated this figure in a letter to Isaac Asimov shortly afterward (Roddenberry attended the protest), writing that:

[…]about 300 students from California Institute of Technology, supported by students from other local colleges, marched on NBC West Coast headquarters in Burbank.”[57]

It’s been claimed that there were also protests by Berkeley students (marching on NBC’s San Francisco area affiliate, KRON) and by MIT students (marching on NBC in New York) but we have, to-date, been unable to locate any contemporaneous accounts— let alone any indication—of the attendance at these supposed protests.

“It was much more expensive than the average show.”

“They were trying to shoot half a science fiction movie every week.”

The financial pain was unbearable for Desilu. They were now making the two most expensive shows on TV.

“It was actually a tie between Star Trek and Mission: Impossible.”

Again, with this date-challenged mess…when are they referring to? Because in the 1967–68 season—as the Paramount deal was being made—Desilu was also producing Mannix, a show equally as expensive as Mission: Impossible and sometimes moreso.

And Mission and Mannix were both significantly more expensive programs to produce than Star Trek, with average costs $10-20k above Trek’s. CBS paid more than NBC did, but they were all expensive shows and all deficit-financed. The big difference? They had better ratings and made more money than perennially low-rated Trek.

“Lucy’s big gamble, Lucy’s big risk, did break the studio. It did break Desilu."

The Big Lie.

In fact, from 1954-1967, Desilu was profitable every year but the one before Roddenberry arrived on Lucy’s doorstep (1963).

Desilu was in the black when Star Trek was in production.

Desilu was in the black when the deal to sell to Gulf & Western and merge with Paramount was closed, to the tune of $1,269,196 in 1967—the studio’s most profitable year in a decade.[58]

Let’s say it again for all the “experts” who can’t be arsed to do actual research:

DESILU WAS PROFITABLE WHEN SOLD.

STAR TREK DID NOT BREAK IT.

<AHEM>

No Laughing Matters

There was trouble, and it had something to do with tribbles.

“Roddenberry had been away for a few weeks, and he came back and he heard laughter coming from stage nine, which is the Enterprise stage.”

“The scene where Kirk gets the cargo open and the tribbles bury him up to his neck. Coon couldn’t help it. The take was so funny, and Shatner was so funny.”

Put your Spocking Caps on, FACT TREKkers, and let’s think logically here:

Soundstages are, as their name suggests, soundproofed.

So the only way Roddenberry was hearing laughter is if he left his office in E building, walked across the lot, and went into the soundstage.

…Also, the space station sets were erected on Stage 10, not 9. We checked…of course.[59]

But to Gene, this was no laughing matter.

“Gene never wanted Star Trek to become silly.”

If Roddenberry had concerns that Trek—which had previously been nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Dramatic Series—might be damaged by going too far into comedy, he’d have had every right to be. The example of Batman loomed large: initially a gigantic hit and pop culture phenomenon a half season before Trek hit the airwaves, its Bat-ratings had Bat-fizzled on its Bat-channel of ABC by the end of Trek’s first season. Many shows had mimicked its over-the-top style to their detriment, including the aforementioned former-hit The Man From U.N.C.L.E., which went camp and down the tubes (a late-stage correction away from comedy proved too little too late and the show never rebounded). And Batman was on its last legs even as writer David Gerrold’s flat cat copies hit the airwaves. If anything, Batman and its imitators were a cautionary tale.

And speaking of Gerrold, let’s see how he recounted his first meeting with the Great Bird of the Galaxy, as written in the early 70s:

We shook hands. (Mine shook without any help.) He said, “Hey, you wrote a good script there. Very nice.”[60]

Assuming Gerrold’s account is accurate, that’s a point against the Bird being anti-comedy: he liked the script.

If anyone is on the record as anti-Tribble it’s Associate Producer Robert H. “Bob” Justman, who wrote he had “never liked David’s original ‘Tribbles’ script for the first series.”[61] Furthermore, there are plenty of memos demonstrating that Justman set the airdate schedule with NBC,[62] and “Tribbles” was scheduled to air during the low-viewer period between Christmas and New Years.

Star Trek was exploring new directions, and Gene wasn’t happy to find his writers dancing to a different tune. [...] So he called in his showrunner to course correct, but Gene Coon wasn’t exactly receptive.

“Gene Coon said, 'If I can’t run the show, I’m walking.'”

Complete hogwash.

There’s zero evidence to support the contention that Coon left the show over the issue of writing "funny" shows and ample evidence to the contrary:

After Coon left Trek—and before his official start at Universal—he did a rewrite of "A Piece of The Action" taking the previously “straight” material in a comedic direction. If Roddenberry was so anti-comedy, he'd have squashed it or had its comedic elements toned down.

The following March (March 6, 1968), long after he left the show, Coon (aka Lee Cronin) was assigned to write "Japan Triumphant" (although he never delivered it), which when conceived in the first season by Roddenberry and Coon—was described as “a sort of comedy show”.[62a]

In “The Letter,” Roddenberry’s August 17, 1967, come-to-Jesus letter to Shatner, Nimoy, and Kelley, he dressed down the leads with the statement, “Gene Coon is ill and leaving, due to emotional fatigue for which you bear some of the blame.”[63][64]

Bob Justman wrote that Coon “had come close to a complete nervous breakdown” through personal stress and overwork.[65]

And most importantly, we asked Andreea “Ande” Kindryd (nee Richardson), Coon's former secretary at both Desilu & Universal, if this story is correct. Her answer, in so many words, "No," and she bristled at people putting words in Coon’s mouth, adding:

It’s not believable to me. I just don’t think the Genes talked to each other like that. Gene R. was a friend and equal[...][66]

In fact, she covers Coon’s departure in some detail in her memoir, and there’s nothing about conflict with Roddenberry, but we won’t spoil it.

However, Gene wasn’t going to let one of Star Trek’s most creative voices just walk out the door.

"The original series wouldn't have been what it was without Gene Coon. Everything from Klingons to General Order Number One."

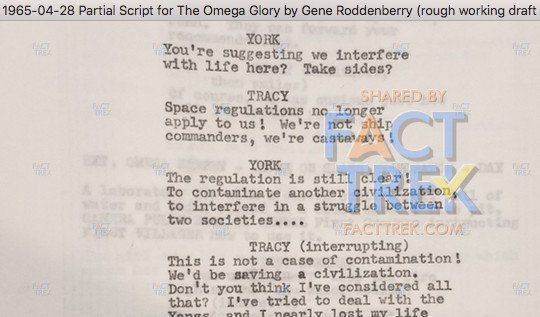

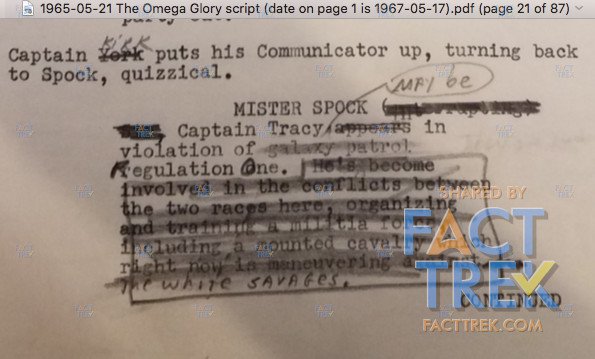

Coon is simultaneously overlooked by many and overcredited by some as regards Star Trek. While he did invent the Klingons, he did not invent “General Order One” aka “The Prime Directive.” That was invented at least fifteen months before Coon joined the staff, in the Roddenberry script “The Omega Glory”—originally one of three scripts written from which NBC selected the second pilot—where it was “Regulation One.” Below are script excerpts illustrating this.

Such misconceptions occur because audiences only see the finished episodes, and from the names on the writing credits may assume that the people credited created all the things in that segment. But TV writing credits aren’t always so straightforward, and lots of ideas are batted around internally. Without access to the production documents, it’s difficult to tell which idea originated with whom.

The Kiss Off

Having survived the kiss of death from the network, Gene pulled out all the stops for season three with a kiss of his own.

“This is the first interracial kiss on television.”

Let’s cut to the chase about whether or not Roddenberry was behind this. He once said:

"I was very annoyed by the way it was handled. The fact that anybody had taken out an advertisement — they should have done it and not advertised in Variety — 'see how brave we are.' […] I didn't feel it was worthy of an ad. I felt it was something that should have gone on all the time, and I felt out of camera range on the vessel, it of course did."[67]

Roddenberry was effectively off the lot by this point (he’d yielded his E-Building office and taken a small office across the lot which he reportedly rarely used) and not as actively involved as he had been in previous seasons. This kiss was almost certainly third-season producer Fred Freiberger’s baby.

This is a much bigger topic for another time, but the historicity of this “first” claim is and remains dubious.

However, there was still no meeting of the minds between Gene Roddenberry and the network. And when NBC decided to move Star Trek to Friday night, Gene drew a line in the sand.

“If you put it at this time slot, I am gonna step back. I’m not gonna be as involved as I was.”

“He drew a line in the sand like Picard would do later on.”

“But they still did it.”

“And said, well, okay, they called my bluff. I’m out of here.”

And, again, we’re back at this confused timeline. The Center Seat makes it seem like the move to Friday and the move to the 10 p.m. time slot were one and the same, but, as per the Laugh-In story above, it was not.

As to Roddenberry drawing “a line in the sand,” consider this: by Nov. 21, 1967, months before production of the second season had ended, Roddenberry had already renegotiated his previously exclusive contract with the studio to become non-exclusive, so he already had a toe out the door months before the 10 p.m. time slot was stet.[68]

When NBC shifted Trek to 10 p.m. NBC’s Mort Werner reportedly met with Roddenberry to discuss.[69] Perhaps this is when Roddenberry proposed coming back to produce the show himself if NBC would relent on the new time slot.

Again, as presented in The Center Seat, it’s tall tales to tell Trekkies how hard he had to fight the mundanes who didn’t understand their show…said mundanes being big bad NBC.

“Gene used to tell a story of how the ratings people come running into the suits at Paramount TV and say, ‘My God, you’ve got the perfect show! And look at this, it’s hitting all the demos. Everything we wanna hit, it’s getting to the right audience.’

And the name of the show was…

“Star Trek. Oh, we canceled it last year.”

Ah, this old chestnut. Just ‘cause Roddenberry claimed it doesn’t “make it so.” Demographics weren’t some new thing that “missed it by that much” for Trek. The press was discussing Gunsmoke’s poor youth demographics late in Trek’s first season.[70] Our friends over at Television Obscurities dismantled this myth years ago. We’ll direct you to them to ‘splain it. (link)[71]

45 in 42

So there you go. 45 dubious items in a ~42 minute program…and we didn’t bother to hit every single factual error, just the notable ones.

We hope this little game of Whack-A-Myth has given you a better sense of how oft-told tales fall short, and that the even “Trek fandom’s top analysts” aren’t necessarily accurate…especially when filtered through an editorial thresher.

The danger with the approach taken by The Center Seat is that oral tradition about pop culture easily teeters into comforting fan fiction. And that’s just where the show lands.

So, let’s all be more discriminating consumers, because mythology isn’t history, and bullshit is fertilizer that smells and tastes bad.

—30—

In upcoming FACT TREKs we’ll be taking a look at some of the whoppers we only touched on, here, including the credibility of many innovations laid at Desilu’s door and on Desi Arnaz’s head.

Our conclusion about episode 1

Revision History

2022-01-04 Original post.

2022-01-05 Typos and other errors corrected.

2022-01-06 Additional information and an image added to the section on the letter writing campaigns and the confusion as to which yielded the unlikely “million letters” that is so firmly entrenched in Trek mythos.

2022-01-07 Section on the “million letters” revised to include information supplied by Star Trek Lost Scenes co-author David Tilotta regarding NBC’s published comment in TV Guide regarding the “Save Star Trek Campaign”.

2022-01-09 Added quote from Bernie Weitzman regarding the terms of the CBS development fund.

2022-01-18 Added comment by Bob Justman as to why Coon left Star Trek. Added information and photo about Laugh-In opposite Lucille Ball’s shows. Corrected some footnote numbering.

2022-03-02 Minor corrections made. Citation 69 inserted and text revised to clarify the situation concerning Roddenbrry’s so-called “line in the sand”.

2023-12-04 Minor tweaks for clarity and an added citation about a story memo re “Japan Triumphant”.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to FACT TREK Associate Ryan Thomas Riddle for his invaluable input and edits. Follow his adventures through time and space on Twitter (link) and see his work on his homepage (link).

Thanks also to FACT TREK Associate Angela Edington-Molyneux for her input on the introduction.

Television Obscurities for their great articles, one of which we cited. Read their stuff.

End Notes & Sources

[1] ‘I Love Lucy’ Tops Nat’l Nielsen Poll, Daily Variety, April 18, 1952, p.8.

[2] CBS’ TOP SKEINS BY DECADE, Daily Variety, October 30, 2003, p.A2.

[3] Nielsen to Get Off Sofa, Into Bars and Gyms, Louise Story for The New York Times, April 13, 2007 (link).

[4] Nielsen will soon include out-of-home viewers in its ratings, Market Watch, September 11, 2019 (link).

[5] Hollywood Inside, Daily Variety, June 3, 1949, p.2.

[6] ‘My Little Margie’ Replaces ‘Lucy’ for Summer—’Celebrity Time’ Alters Its Format, New York Times, June 20, 1952, p.33.

[7] Desilu Closes Buy Of RKO Lots; Must Alter Studios' Tag, Daily Variety, December 12, 1957, p.3.

[8] This Day in Aviation, 26 October 1958 (link).

[9] The Secret Weapon of 117 (aka The Secret Defence of 117) on IMDb. (1956) (link) FACT TREK NOTE: We have a copy of this script and plan to cover it in a future article.

[10] DEFENSE DEPT. REFUSES TO OK 'LIEUT.' SEG, Daily Variety, February 19, 1964, p.1.

[11] James Van Hise, The Man Who Created Star Trek: Gene Roddenberry (1992), p.16. Roddenberry is quoted as saying:

I had only one thing I could do...I went out to [the] NAACP, and an organization named CORE, and they lowered the boom on NBC. They said, 'Prejudice is prejudice, whatever the color.' And so we were able to show the show.

[12] Stephen E. Whitfield & Gene Roddenberry, The Making of Star Trek, (1968) p.34.

[13] In its 1962–63 season The Defenders ranked #18, making it a top-20 show. Tim Brooks and Earle Marsh, The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows 1946-Present (Seventh Edition, 1999), p.1247.

[14] James Van Hise, The Unauthorized History of Trek, Pioneer Edition, 1995, p.20.

[15] David Alexander, Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry, (1994) p.188. (1995 paperback p.204).

[16] David Alexander, p.189. (1995 paperback p.205).

By March 11, 1964, he had the concept down in sixteen pages, enough to show to industry buyers. He called it Star Trek.

On April 24, Gene sent a check for two dollars and the required three copies of the series prospectus to Blanche Baker at the Writers' Guild of America, West, Inc. to protect the concept of Star Trek from theft.

[17] Stephen E. Whitfield & Gene Roddenberry, The Making of Star Trek, (1968) p.38, 41.

[18] Solow & Justman, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, ISBN 9780671896287, p.16, 19.

[19] Solow & Justman, p.XVIII.

[20] Hitchcock’s Show Is Moving To N.B.C., Val Adams for New York Times, March 3, 1964, p.71.

[21] Is CBS Losing Comedy Stars?, Paul Jones for The Atlanta Constitution, February 10, 1964, p.3A.

[22] Solow & Justman, p.15.

[23] Letter to Alden Schwimmer from Gene Roddenberry, May 4, 1964, Icons of Hollywood Auction.

[24] David Alexander, p.189 (1995 paperback p.205).

[25] Ad: “Desilu welcomes Goodman & Klein, Jurow, and Roddenberry, Daily Variety, June 2, 1964, p.12.

[26] Joel Engel, Gene Roddenberry The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek, 1995 (mass market printing). p.40.

[27] Solow & Justman, p.5, 13.

[28] Cost-Revenue Analysis. 1968 (approximate, document undated) Paramount Television Division Cost-Revenue Analysis for Mission: Impossible, Star Trek, and Mannix, UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[29] Desilu Year Net Rises To 830G; Eye Diversification, Daily Variety, August 17, 1966, p.1, 10.

[29a] Broadcasting. Stockholders get on the Ball, p.66.

[30] Solow & Justman, p.16.

[31] 1964 (undated) Possible Casting Suggestions for First Pilot, UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[32] William Shatner with Chris Kreski, Star Trek Memories (1993), p.41, 85.

[33] “To Set It Right,” The Lieutenant, on IMDb. (link)

[34] Cost-Revenue Analysis. ibid.

[35] Desilu's Final Revised Production Budget, dated November 25, 1964, anticipated the first pilot would cost $451,508. Cost overruns sent it well over that figure, but even if the company had delivered the pilot exactly as planned, Desilu would have deficit financed it to the tune of $266,508. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[35a] Coyne Steven Sanders and Tom Gilbert, Desilu: The Story Of Lucille Ball And Desi Arnaz (1993), p.279 (new and expanded edition, 2001).

[36] Solow & Justman, p.60, 61.

[37] 333 Montgomery, on IMDb. (link) The program was shot as a pilot for NBC but “burned off” by being aired as a segment of Alcoa Theater (1957–60).

[38] Police Story, on IMDb. (link) The program was a 1965 pilot for NBC but “burned off” as part of a “sneak preview” week in 1967.

[39] Stephen E. Whitfield & Gene Roddenberry, p.135-136.

[40] Cost-Revenue Analysis. ibid.

[41] Solow & Justman, p.277–278.

[42] Paula M. Block with Terry J. Erdmann, Star Trek: The Original Series 365, 2010. From the Introduction by D.C. Fontana.

[43] The weekly cost summaries for the weeks ending January 14, 1967 and February 4, 1967 show the first season series episode budget being dropped from $192,863 to $185,349. UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[44] THE COLOR REVOLUTION: TELEVISION IN THE SIXTIES, TV Obscurities (link)

[45] Those Men From U.N.C.L.E.—Going, Going, Really Gone, By George Gent 1968, New York Times, December 17, 1967, Section A, p.119.

[46] “U.N.C.L.E. Cartoons,” The U.N.C.L.E. Archives, For Your Eyes Only, p.1. (link) Source of images of MAD Artist Jack Davis’ Illustrations of NBC’s 1965-66 Season for TV Guide.

[47] “See MAD Artist Jack Davis’ Illustrations of NBC’s 1965-66 Season for TV Guide,” TV Series Finale, April 19, 2010. (link)

NOTE: The full spread for the week on the website is for USA Central Time zone, which will put most of the programs an hour earlier or later than they appeared in the Eastern and Pacific time zones.

[48] Stephen E. Whitfield & Gene Roddenberry, p.249-250.

[49] Solow & Justman, p.343.

[50] Channel Chuckles for Nov. 19, 1965, by Bob Keane. Image source “U.N.C.L.E. Cartoons,” The U.N.C.L.E. Archives, For Your Eyes Only, p.2. (link)

[51] Solow & Justman, p.380. Specifically:

[A]ccording to Alan Baker, who was Director of Program Publicity for NBC during those years, all reports of the Star Trek mail “counts” were greatly inflated. Baker was responsible for seeing that each and every letter received a reply. “During those days, NBC was very meticulous about responding to our viewers,” states Baker. “I’m sure the other networks were also, but at NBC it was a very strong point.” […] “During the months of January and February, 1968, NBC’s Star Trek mail count totaled 12,000 pieces,” Baker states. […] If we had received the amount of mail the Star Trek people said we received, believe me, I would have known about it.”

[52] Star Trekkers Are Restored.” Hartford Courant. 17 Mar. 1968: 12H.

Star Trekkers Are Restored - In response to viewer reaction In support of the continuation of the NBC's "Star Trek" series, plans for continuing the space adventure series in the fall have been announced by the network. Earlier the series had faced cancellation. Since early December, NBC has received 114,667 pieces of mail in support of "Star Trek", 52,151 in the month of February alone. NBC said that "Star Trek" would be colorcast on a different day and in a new time period Mondays, 7:30-8:30 p.m. the fall. This season the series Is being presented Fridays, 8:30-9:30 p.m.

[53] TV-Radio: “End of Trek,” Newsweek, January 29, 1968, p.54.

[53a] Letters, TV Guide for March 6–13, 1968, p.A-2.

[54] Roddenberry’s ‘Folly’, Enterprising Star Trek Taps TV's Potential, Don Page for Los Angeles Times, Aug 13, 1968, p.F1

[55] From the Archives: 1968 protest against possible Star Trek cancellation, Los Angeles Times, Jan. 6, 1968: Caltech students protest the rumored cancellation of the “Star Trek” TV series outside NBC Studios in Burbank.(link). The article mentions “over 200” protesters.

[56] COSMIC ISSUE---TV SERIES: Caltech Joins Protest Trend, Jerry Ruhlow for Los Angeles Times, January 8, 1968, p.3.

[57] Letter from Gene Roddenberry to Isaac Asimov, January 9, 1967 (Roddenberry 366 Project).

[58] Edwin Holly collection of Desilu and First Artists reports, AMPAS library

[59] Shooting Schedule for “The Trouble With Tribbles,” August 21, 1967, UCLA, Robert H. Justman Collection of Star Trek Television Series Scripts, 1966-1968.

[60] The Trouble With Tribbles the birth, sale, and final production of one episode, by David Gerrold, 1973, Ballantine Books edition, p. 248; BenBella Books edition, 2004, p.268.

[61] Solow & Justman, p.334.

[62] UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[62a] Memo from Roddenberry to Coon, subject “STAR TREK STORIES Discussed” dated 12/1/66. The memo summarizes a meeting the two men had discussing potential story springboards, including “Japan Triumphant.” UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[63] Letter from Gene Roddenberry to William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, DeForest Kelley (aka “THE Letter), August 17, 1967, UCLA, Gene Roddenberry Star Trek television series collection, 1966–1969.

[64] Roddenberry Joins Ranks of Disenchanted TV Creators, Daily Variety, January 1, 1968. Refers to Roddenberry, Coon, and another person being hospitalized due to overwork.

[65] Solow & Justman, p.349.

[66] Andreea Kindryd, via personal correspondence with FACT TREK.

[67] William Shatner with Sandra Marshak and Myrna Culbreath, Shatner: Where No Man...: The Authorized Biography of William Shatner (1979), p.154.

[68] RODDENBERRY GIVEN NEW PAR TELEVISION DEAL, Daily Variety, November 21, 1967, p.1, 14.

[69] ‘Trek’ May Be Off NBC’S Track In Fall, Daily Variety, March 18, 1968, p.1 & 26.

[70] Why Gunsmoke Almost Fell--Young People Don't Watch It, Press and Sun Bulletin, Sun, March 17, 1967, p.40.

[71] “A LOOK AT STAR TREK,” section “What About Demographics? TV Obscurities. (link)

Until Next Time, FACT TREKkers.

Same FACT TIME

Same FACT CHANNEL.